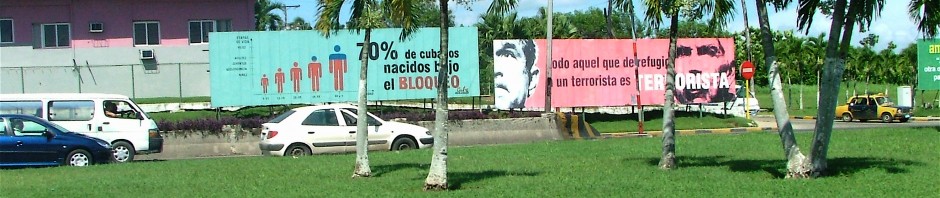

This year is the 52nd anniversary of the Cuban Revolution, as signs trumpeted from Havana all the way through the countryside to Ciego de Avila, 460 kilometers away. Fidel, Ché and Raul gaze down from murals, statues and billboards as ubiquitous as the antique cars. Fifty two years of victories, they proclaim, The fight continues, The Revolution is everything, we’re reminded. Slogans pop up at us around every corner.

At the airport, we ask someone in a uniform how much we can expect to pay for the ride to our hotel. Taxi and tour buses are the only transportation options between the airport and Havana. “Twenty five dollars,” he says. “Thirty at the most.” The taxi driver starts pointing out statues and sculptures of the revolutionaries right away.

When we arrive at our hotel, he demands sixty bucks; we pay, knowing we’re being fleeced. Since we live in a third world country, we’re very much aware that perceived wealth is often a temptation to extortion and theft by the destitute and some who think the world owes them. Not that cons are only perpetrated in third world countries…

We wonder what the people really think. They’re poor, for the most part. As we wander the city in a shriveling, withering heat, we notice people leaning from the balconies of dilapidated buildings that clearly aren’t air-conditioned. Some of these buildings where people live look condemned, and the odor as one passes in front of them stops the breath. Children and old folks not selling things are begging -off the beaten track.

Guide books warn of elaborately planned cons that await unsuspecting and kind-hearted tourists. Here’s the one that Jack fell for: the young couple, dressed in rags, and carrying a similarly dressed infant, beseech him. “We can’t pay for diapers for our child,” they say, holding the dingy child up for inspection. “Yes, of course,” says Jack, as he’s led past several stores to one where the owner asks thirty dollars for the box. Fleeced again.

In Havana, the folks we speak to seem fiercely proud of the Revolution, and of the government, despite the poverty. Castro and Ché are still heroes. Ivan, who drives us through the streets of Havana in his horse-drawn buggy, speaks reverently of the Revolution, though his words have a hollow ring. He mentions it often, and invokes the sacred names, but the subtext is that the Revolution put a thriving city out of business. When he pulls from his memory dates of business closings then dates of subsequent re-openings, decades later- that begs the question: how can they think the revolution was a good thing?

Ivan seems ready to spit as he speaks of the days of Batista, the dictator deposed by the Revolution. Those were the days of big-spending gangsters, movie stars, and writers. When Batista escaped, Ivan said, he took 300 million dollars with him. The US liked him, because he let our companies rape Cuba to enrich himself, to the destitution of the population. Folks like Ivan know that they’re better off now than they were then. If they blame us for their impoverishment, they don’t show it. They’re optimistic about the end of the embargo. Ivan mentions that Americans- his word- regularly distribute food here at the harbor.

Clearly, some Cubans are wealthy. We see them in the restaurants. We’d heard from the Lonely Planet and friends who’d been there before us, that the restaurants are state owned, uniformly terrible, and expensive. On a recommendation from the bartender at our hotel, we walk a few smelly blocks along the harbor to a newly restored building, freshly painted in a pastel yellow, and enter the restaurant after an effusive greeting from the tuxedoed man at the door. The restaurant is the Sociedad Asturiana Castropol, on Calle Malecon 107.

The waiter, a charming young man with an enduring smile, presents us with the menu, with a flourish. The specialty of the house is grilled meats. The smell of charcoal-grilled meats envelops us. The restaurant is exquisite, albeit hot. Jack wants pork chops, and asks for two. When the order arrives, on the plate sits at least seven pork chops, along with artful garnishes, and a medley of freshly grilled veggies. I order a steak, which also arrives elaborately garnished and grilled to perfection. The prices please and surprise: including our cocktails, the check comes to 28 dollars.

We notice a constant stream of people climbing the steep stairs to the second floor. An entirely different restaurant awaits upstairs, and we determine to return the following night.

On the second night, we return to our hotel bar to have mojitos, thank the barman and tell him we liked the restaurant so well that we’re going back. At the restaurant, we climb the stairs, following a shapely young woman outfitted in a very tight white business suit. I’d die for her figure. Another young woman plays familiar tunes while we dine in air-conditioned bliss. Jack has a shrimp-stuffed filet wrapped in bacon, and declares that he’s never had a finer meal, at the same low prices as downstairs. I’m beginning to feel the first pangs of a bug I’ve picked up, and can’t eat my beautifully garnished white fish with salmon mousse. I do, however, manage to polish off most of the bottle of red Malbec we order, while Jack sips the rum and midori cocktails the waiter has pressed on us.

When the maître d’ appears, I ask where the chef has been trained. The maître d’ and chief answer simultaneously, “Here.” Then, after a few beats, finish the sentence. “And at the Cordon Bleu.” They’re part of a group of friends who own this restaurant, and the one downstairs, they tell us.

They pay rent to a co-op, and run the restaurant as they please. The government is in no way involved. Is this private enterprise after all, we wonder? Ivan Rodriguez, Chef and Chef and Sommelier Maître Bequet Joel, confirm our suspicions that many of the clientele are wealthy and influential Cubans. “When the famous Cubans eat here,” they tell us, others want to come too.”

Cuba has been successful in creating a country where medicine is accessible to all; however, doctors there are as impoverished as others. The taxi driver who drives us the last 60 kilometers to the resort where we head after Habana, tell us that, though his wife is a doctor, and he drives the taxi, they wonder where the food and clothing will come from for the family. He too, hopes the embargo will end soon.

On the country roads we traverse, traffic mostly takes the form of horse and buggy. Farmers stand along the road, arms outstretched, holding out mangoes and papayas. It strikes me as painful that they have no better venue than this desolate stretch of highway.

I hope Casto makes good on this week’s promise to encourage private enterprise. And I hope we lift the embargo. They deserve better.

Hi Myra, sounds like you found better restaurants than I did on my trip to Cuba.

How can they think the revolution was a good thing? I think it’s a lot like China, in that the Chinese say that Mao restored their pride. After all, the revolution was a nationalist revolution and didn’t take on its socialist characteristic until later.

Hi Conor. That makes sense. Thanks for stopping by.

Hi Myra, sounds like you found better restaurants than I did on my trip to Cuba.

How can they think the revolution was a good thing? I think it’s a lot like China, in that the Chinese say that Mao restored their pride.