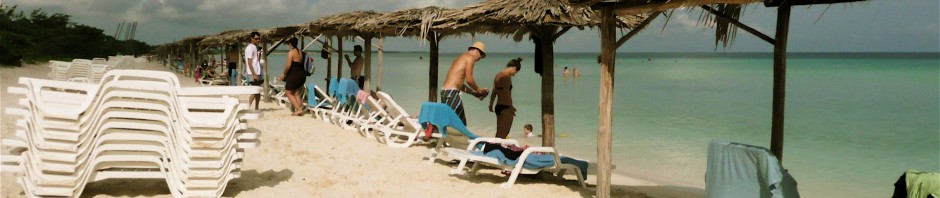

I’d have felt boorish if we’d visited Cuba and not checked out Havana, but the words “beach vacation” ricocheted around my brain. After all, this trip was my escape from the rainy season. I booked three nights in a hotel in Havana, and four nights at an all-inclusive beach resort. After two days in hot Havana, I yearned for the beach, sea breezes and cool water. I dreamt of sitting under an umbrella reading while listening to the soft sounds of the surf.

I booked us into the Hotel BlueBay Cayo Coco. Dreams of horseback riding on the beach roped me in, so did the gazillion water activities offered by the hotel. All-inclusive didn’t worry me: I’d once been to an all-inclusive Sandals in Jamaica, and loved it, despite my determination not to.

But my choice of resorts in Cuba seemed ill fated from the start. I didn’t notice, until we arrived in Havana, that Cayo Coco was almost 500 kilometers from the city- one-third the distance between Costa Rica and Havana.

We took a six-hour bus trip from Havana to Ciego de Avila, smack in the middle of rural Cuba, and then a taxi for the last 60 kilometers to BlueBay. We paid sixty dollars for the taxi, and sixteen each for the bus. I began smacking myself for not having booked a flight.

We arrived at BlueBay just before dinner, having spent an entire day in transit. The resort spread out in a circle from the spacious main reception area. We checked in, and hopped into a golf-type cart with a smiling guy called Wilbur, who pointed out the restaurants and snack bars, and said we could get food and drink 24-hours-a-day. Yippee. He assured us that our room was in the very best location. Hm. Bet he says that to everyone.

Our room was spacious and clean, with a view of the bay and mangrove marshes from the private balcony, but we couldn’t adjust the air. A call to the front desk brought a technician who lowered the room’s temperature, but couldn’t adjust the controls. He said, “Call tomorrow, and the engineer will fix the problem.” We did call the next day, and reported that we couldn’t adjust the air, and had no hot water. We never saw the engineer, and the controls weren’t fixed, but the room was cool enough for us, and the hot water flowed, so we didn’t waste time on further calls to the front desk.

We followed a parade of people to the main dining area. On the way, we passed several scowling couples. I wondered, what’s with the long faces? “These people are not supposed to be dour- they’re on vacation,” I said to Jack. We’re friendly, and we automatically smile at other folks, but these people didn’t make eye contact. They stared straight ahead, as though led on an invisible leash.

We found a spot for two, near the window, then set off to explore the buffet tables. We saw mountains of food: fish, chicken, sausage, and various other meats adorned one end of the oblong table, with salads, veggies and fruit completing the circle. Chefs stood, in their foot-long cylindrical white hats, at a pasta center, taking orders for a comprehensive selection of noodles and sauces. At the opposite end of the room, other chefs stood, grilling meat and seafood to order. We pronounced the food over-cooked and devoid of seasoning. I didn’t mind, though, because I suffered pains in my stomach and other symptoms that attend unwanted microbes in the gut, and I couldn’t eat.

The next day, we passed more glowering people on the way to the dining room. As I surveyed the groupings of pastel buildings, I thought: this is like the Prisoner’s Village!

The village in question, a seaside resort in an unknown location, was the setting for the late sixties British TV series, The Prisoner. BlueBay had that same surreal quality, and though the inmates weren’t nearly as exciting as the former spies and operatives that populated the village in the series, they might easily have been hypnotized, or programmed for submission.

I began listening to the languages the prisoners were speaking. Ah! English! “I wonder if they’re American?” I asked Jack, tilting my head back, so he’d know I referred to the couple behind me. “No. Probably not. They must be Canadian.” Our fellow prisoners were largely French and English Canadians. The Spanish speakers were European, we decided. This place certainly isn’t Cuba, we mused.

We began to notice the disproportionate number of obese people at the village. That’ll happen when folks are force-fed institutional cooking. We sat in awe as we watched legions of over-sized people following their bellies around the buffet tables.

We finally talked to the young couple who had been sitting behind me in the dining hall. They were Canadian, and friendly, as well. They were inmates, like us, who marveled at the terrible food and miserable populace.

On our last day, I ventured to strike up a conversation with a single inmate who sat alone by the pool. His name was Marc, and he was the friendliest prisoner I’d so far encountered. We commiserated at length about the village and the other inmates, and we learned that he, like us, had begun planning an escape. We spent the day together, we three, and contrived a future friendship away from the village.