About a week after we moved to Japan, my daughter, Bonnie, and I experienced our first earthquake. As we sat on the floor, Japanese style, our legs tucked under the kotatsu for warmth, the apartment began to sway.

“Look at that,” said Bonnie, eyes on the table, “the water is sloshing around in the glass!”

“Aren’t we supposed to run outside?”

We shot outside in an adrenaline-induced burst. Imagine our surprise when we noticed nary another person. The Japanese, we learned, live with lots of tiny earthquakes, and barely notice them.

One day, as I sat counseling a student on the 13th floor of an office building in Tokyo, the table began to dance. Like a greyhound at the starting gate, I quivered in anticipation of flight, until I noticed that my student sat unfazed across from me. “The table!” I babbled. “It’s an earthquake!”

The student laughed. “We’re used to it,” he said. “Don’t worry. If it’s a big one, you’ll hear it first.” Try as I might, I couldn’t imagine the sound caused by the ripping of the earth, and I hoped I never would.

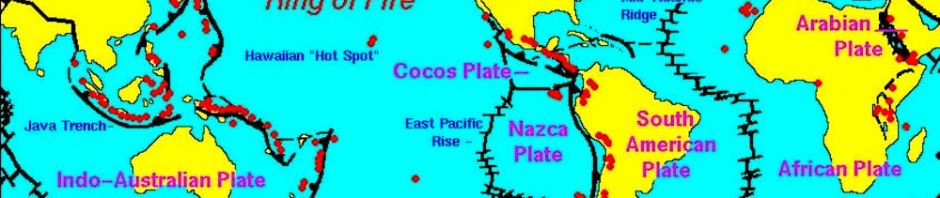

A decade after my escape from earthquake-prone Japan, I retired to the opposite side of the Pacific Ring of Fire, the crucible of seismic activity that is Costa Rica. Here, I’ve lived through a few earthquakes that caused my dishes to rattle and my adrenaline to spike, but I’d never heard one until last week.

When my desk began to shudder, I rose quickly, but rather than running the few feet to the door, I froze in place, trance-like, in front of my Imac. I looked around and wondered if I’d be swallowed up this time, part of a trembling tableau. I didn’t seem to care.

A growl seeped up from the earth, turned into a rumble, then a roar. When the tiles seemed to bounce beneath my feet, I thought, “I’m riding the floor!” A freight train careening through the place wouldn’t have surprised me. Outside, the dogs barked furiously, snapping me out of my trance.

Jack raced into the kitchen and planted himself in front of our shelves of glasses and plates. As I lurched towards him, the earth quieted once more.

I’ve learned a little about earthquakes since then. At a gathering of gringos, we recounted our stories. We’re still not sure about the epicenter, which some claim was Puriscal, where we live. We were lucky, they said, because the quake was so deep. And it was big: 6.0 on the Richter scale.

It turns out that there are about three million earthquakes around the world every year. In other words, on any given day, there’s a 100 percent chance of an occurrence somewhere. I think I’ll stay here in Costa Rica, but next time, I’m outside!