My nephew Jake, or Jake-o-rama, as I like to call him, is autistic. He was diagnosed when he failed to develop language skills at the appropriate age.

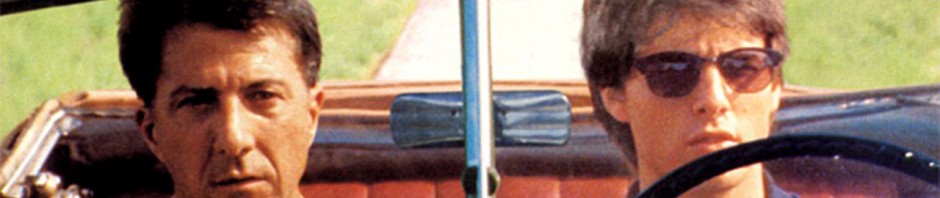

Autism is a relatively new diagnosis, although it was first described in the forties. In 1988, in the film, Rain Man, Dustin Hoffman portrayed a savant : an extraordinarily gifted, yet developmentally disabled person. Ironically, the real-life Rain Man was a savant, but not autistic. Nonetheless, he served to awaken the world to autism, an ambiguous developmental disability.

Despite his pervasive developmental disorder, Jake graduated from Philadelphia’s prestigious Girard Academic Music Program (GAMP) a year ago. Like many others on the autism spectrum, my nephew has musical talent, and a prodigious memory for all things related to trains and buses. He’s a friendly and enthusiastic guy, but like many others who suffer from autism spectrum disorders, he displays a marked lack of social skills. He can shake your hand and look you in the eye, but those are skills he’s learned.

That’s because autism affects executive function, the set of critical cognitive skills that we rely on to integrate past knowledge with present circumstances, to make decisions, plans, schedules; to organize, hypothesize, analyze; and to control our behavior. With impaired executive function, we are unable to comprehend or relate to the feelings of others: there’s no sympathy or empathy. So Jake can be difficult as well as delightful.

Autism is part of our lexicon now. We’ve learned, often through movies and TV, that those on the highest end of the spectrum can be indistinguishable from other geniuses and prodigies. Hollywood has produced more than ten films about autistic people, including Forrest Gump, I am Sam, Little Man Tate, and What’s Eating Gilbert Grape.

We now conjecture that characters from literature, stage, film– even cartoons– were autistic. The list of historical figures who are now suspected of, or credited with having high-functioning autism is impressive. Among them: scientists Einstein and Alexander Graham Bell; musicians Mozart, Beethoven, and Mahler; literary giants Emily Dickinson, George Bernard Shaw, and so many more of my particular heroes.

Additionally, there are famous high-functioning people like Temple Grandin, a scientist, inventor and university teacher who was last year named as one of the 100 people who most affect our world, and about whom an HBO special was made. Autism spectrum disorders, it seems, are a lot more pervasive than many of us imagined, particularly among high achievers.

A smidgen of knowledge has led to speculation among my friends as to which of us is autistic. Remember that kid you knew in high school or college who always got straight A’s, but never fit in? Autistic! That cousin who could tell you one joke after another for hours on end without cracking a smile, or listening to your responses? Autistic. Your old boyfriend, the close talker who couldn’t figure out why you were always moving away from him, your Mister-Spock-like algebra teacher, your unruly sister, autistic.

The public has embraced high-functioning autism. We wonder, maybe, if it’s the way to be. Bill Gates shows up on lists of public figures who might be autistic. So do Bob Dylan, Woody Allen, Al Gore and Garrison Keillor. Maybe it is the way to be.